LL(1) Grammars for Predictive Parsing

Motivation

Parsing is the problem of, given a sequence of terminal symbols (a string) $w$, determining if $w$ is in the language of a grammar and, if so, constructing some representation of its structure.

There are lots of methods that have been designed for parsing strings according to a grammar, but we will be studying just one, which happens to be one of the most widely used in practice. This method is called predictive parsing, and many of the programming languages you regularly use are parsed by some variant on a predictive parser.

Suppose we have a grammar such as this simple grammar for Boolean expressions:

\[B \Coloneqq \tt \mid \ff \mid (B) \mid B \andop B \mid B \orop B\]If you fix a string (the string you want to parse) then you can try to check whether or not it is in the language described by the grammar by constructing a derivation. However, a key difficulty is that, from the very start, there are choices - which production rule should we use?

For example, consider trying to derive the string $\tt \orop \ff \andop \tt$. We start from $B$, but which rule should we pick? Should we pick the first rule \(B \Coloneqq B \andop B\) because the string contains the terminal $\andop$? Or maybe we should pick the second rule \(B \Coloneqq B \orop B\) because the string contains the terminal $\orop$? Or the rule $B \Coloneqq \tt$, since that is the first terminal symbol of the string?

Often it can require some human insight in order to make the right choice, and this is not a good basis for an efficient algorithm.

The idea of predictive parsing is that we limit ourselves to parsing grammars for which making these choices is easy.

LL(1) grammars have the property that, at every step of the derivation, which rule we choose is completely determined by a combination of the leftmost non-terminal in the current sentential form (this is the first L in “LL(1)”), and a fixed size prefix of the remaining input string, say the single leftmost character (this is the second L and the 1).

The following grammar may look strange, but it is actually equivalent to the previous one, in the sense that they generate the same languages. The start symbol is still $B$.

\[\begin{array}{lcl} B &\Coloneqq& A\ B'\\ B' &\Coloneqq& \andop A\ B' \mid \mathord{\orop}\ A\ B' \mid \epsilon \\ A &\Coloneqq& \tt \mid \ff \mid (B) \end{array}\]We’ll get into how one can come up with a grammar like this in a later lecture, but for now I hope you can simply accept it is an alternative way to describe this language of simple Boolean expressions.

Although it is arguably less readable, this grammar has the advantage that it is LL(1), i.e. for any input string in the language, we can construct a derivation in which the choice of production at each step is completely determined by the leftmost non-terminal in the sentential form and the first character of the remaining input. Let’s try to derive $\tt \orop \ff \andop \tt$.

We start from the start symbol $B$ and immediately we have no choice, we must derive:

\[B \to A\ B'\]Next, we consider the leftmost non-terminal in the sentential form we have now reached, which is $A$. Here we have a choice of three productions to choose from, and so we also consider the first letter of the remaining input. The first letter of the input is $\tt$ so there is really only one applicable choice, namely the production $A \Coloneqq \tt$:

\[A\ B' \to \tt\ B'\]All other choices for $A$ would result in strings starting with a terminal symbol other than $\tt$ and thus be inconsistent with the input string. In other words the production rule was (uniquely) determined once we knew the nonterminal we are trying to derive from and the first letter of the input.

Now derived that first letter $\tt$, so we remove it from the input and continue to try to derive the remainder $\mathord{\orop}\ \ff\ \mathord{\andop}\ \tt$. The next leftmost non-terminal is $B’$ and here we have three productions available for $B’$. So we consult the first letter of the remaining input, which is $\orop$. Of the three possible production rules for $C’$, only one can potentially derive a string starting with $\orop$. So the choice of rule $B’ \Coloneqq \orop\ A\ B’$ is uniquely determined:

\[\tt\ B' \to \tt\ \mathord{\orop}\ A\ B'\]Now the leftmost non-terminal is again $A$ and again we have three choices, but a glance at the first letter $\ff$ of the remaining input tells us that the second of the three rules for $A$ is the correct one, and we derive:

\[\tt\ \mathord{\orop}\ A\ B' \to \tt\ \mathord{\orop}\ \ff\ B'\]We cross off $\ff$ from the remaining input, and try to derive the rest $\andop\ \tt$. The combination of nonterminal $B’$ and next terminal $\andop$ uniquely determines the rule $B’ \Coloneqq \mathord{\andop}\ A\ B’$ and so we obtain:

\[\tt\ \mathord{\orop}\ \ff\ B' \to \tt\ \mathord{\orop}\ \ff\ \mathord{\andop}\ A\ B'\]Since the grammar is LL(1) and the given string indeed belongs to the language of this grammar, we can continue this strategy and we are guaranteed to construct a leftmost derivation which required no human insight at all:

\[\begin{align*} B &\to A\ B'\\ &\to \tt\ B'\\ &\to \tt\ \mathord{\orop}\ A\ B'\\ &\to \tt\ \mathord{\orop}\ \ff\ B'\\ &\to \tt\ \mathord{\orop}\ \ff\ \mathord{\andop}\ A\ B'\\ &\to \tt\ \mathord{\orop}\ \ff\ \mathord{\andop}\ \tt\ B'\\ &\to \tt\ \mathord{\orop}\ \ff\ \mathord{\andop}\ \tt \end{align*}\]This strategy is something we can turn into an algorithm, and a very efficient and simple algorithm at that.

We’ll see a nice way to implement this algorithm in the next lecture, but for now I want to get a better (i.e. more precise) handle on what makes a grammar LL(1). To do this we have to consider three key properties of non-terminals $X$ in a given grammar, say with start symbol $S$: called $\nullable(X)$, $\first(X)$ and $\follow(X)$.

Nullable, First and Follow for Nonterminals

We’ll use the original one-liner grammar as an example:

\[B \Coloneqq \tt \mid \ff \mid (B) \mid B \andop B \mid B \orop B\]$\nullable(X)$ is a proposition indicating whether or not the empty string is derivable from $X$, i.e.

\(\nullable(X) \;\text{iff}\; X \to^* \epsilon\)

For example, the first grammar above whose only non-terminal is \(B\), \(\nullable(B)\) is false, since the empty string is not derivable.

$\first(X)$ is the set of terminal symbols that start sentential forms derivable from $X$, i.e.

\(\first(X) = \{ a \in \Sigma \mid \exists \beta.\, X \to^* a\beta \}\)

For example, in the grammar above whose only non-terminal is \(B\), \(\first(B) = \{\tt, \ff, \tm{(} \}\) because $B$ derives Boolean expressions which can only begin with one of those terminal symbols.

$\follow(X)$ is the set of terminal symbols that can appear immediately following non-terminal $X$ in a derivable sentential form, i.e.

\(\follow(X) = \{ a \in \Sigma \mid \exists \beta\ \gamma.\: S \to^* \beta X a \gamma \}\)

For example, in the grammar above whose only non-terminal is \(B\), \(\follow(B) = \{),\andop,\orop\}\), as can be seen by the following witnessing derivations, respectively:

\[\begin{align*} B &\to^* (B) \quad \text{with $\beta=($ and $\gamma=\epsilon$}\\ B &\to^* B \andop B \quad \text{with $\beta=\epsilon$ and $\gamma=B$}\\ B &\to^* B \orop B \quad \text{with $\beta=\epsilon$ and $\gamma=B$} \end{align*}\](In this case, all the witnessing sentential forms are obtained after just one step of derivation, but in general it may require many steps.)

If one were to calculate these properties naively, it seems like it would take forever since there are potentially infinitely many derivations to check. Luckily, they can each be calculated by an algorithm. We won’t cover the algorithms because they are not so interesting: in practice you can always use a program to compute them for you, and in this unit you will always be given the three properties directly. Speaking of which, here is a summary:

\[\begin{array}{|c|c|}\hline \text{Nonterminal} & \text{Nullable?} & \text{First} & \text{Follow} \\\hline B & \times & \tt,\,\ff,\,( & ),\,\andop,\,\orop \\\hline \end{array}\]Nullable and First for Sentential Forms

Once we know $\first$ It is useful to extend the definitions of $\nullable(X)$ and $\first(X)$ so that we can ask about the nullability of and the first terminal symbols derivable from, an entire sentential form $\alpha$.

\(\nullable(\alpha) = \begin{cases} \checkmark{} & \text{if $\alpha = \epsilon$}\\ \times & \text{if $\alpha$ is of shape $a\beta$}\\ \nullable(X) \wedge \nullable(\beta) & \text{if $\alpha$ is of shape $X\beta$} \end{cases}\)

The idea is that an empty sentential form is, of course, nullable, and a sentential form beginning with a terminal symbol $a$ is, of course, not nullable. A sentential form beginning with a non-terminal $X$ is a bit more subtle, it is nullable just if $X$ is nullable and the rest of the sentential form is again (recursively) nullable.

It is a good idea to compute the nullability of the right-hand side of each production rule:

\[\begin{array}{|c|c|}\hline \text{Rule RHS} & \text{Nullable?} \\\hline \tt & \times \\ \ff & \times \\ (B) & \times \\ B \andop B & \times \\ B \orop B & \times\\\hline \end{array}\]Clearly, if you start a derivation from one of the right-hand sides of rules for $B$, there is no way to reach the empty string, so all are $\times$.

Next, lets extend the definition of $\first$ from a single nonterminal to a sentential form.

\(\first(\alpha) = \begin{cases} \emptyset & \text{if $\alpha = \epsilon$}\\ \{a\} & \text{if $\alpha$ is of shape $a\beta$}\\ \first(X) & \text{if $\alpha$ is of shape $X\beta$ and $\neg \nullable(X)$}\\ \first(X) \cup \first(\beta) & \text{if $\alpha$ is of shape $X\beta$ and $\nullable(X)$} \end{cases}\)

The idea is that no terminals that can start any sentential form derivable from $\epsilon$. Only the terminal symbol $a$ can start any sentential form derivable from a sentential form already starting with $a$. Finally, the terminal symbols that can start a sentential form derivable from a sentential form of shape $X\beta$ – that is, starting with some non-terminal $X$ – are those that can start sentential forms derivable from $X$ and if $X$ is nullable, then also those that (recursively) can start forms derivable from $\beta$.

Let’s compute the first sets of all the right-hand sides of the rules from the grammar:

\[\begin{array}{|c|c|}\hline \text{Rule RHS} & \text{First} \\\hline \tt & \tt \\ \ff & \ff \\ (B) & ( \\ B \andop B & \tt,\,\ff,\,( \\ B \orop B & \tt,\,\ff,\,( \\\hline \end{array}\]The Parsing Table

Recall that the key idea of a predictive parser (with lookahead 1) is that it tries to derive a given string starting from the start symbol of the grammar and, at each step in the derivation, which rule to choose should be completely determined by a combination of the left-most non-terminal and the next letter of the input.

Building the Parsing Table

Therefore, to check if a grammar is appropriate for predictive parsing, we build a table $T$ that describes the possible meaningful choices $T[X,a]$ of grammar rule for each combination of left-most nonterminal $X$ and next letter of the input $a$.

We define the parsing table, usually $T$, for a given grammar as a 2d array in which each entry $T[X,a]$ is a set of production rules from the grammar, such that some rule $X \Coloneqq \beta$ is in the set $T[X,a]$ just if, either:

- $a \in \first(\beta)$

- or, $\nullable(\beta)$ and $a \in \follow(X)$

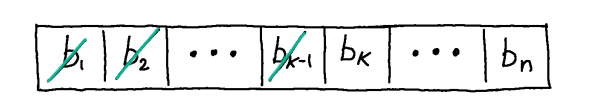

To see why this makes sense, suppose we are in the middle of building a derivation for some input string $b_1b_2\cdots{}b_{k-1}b_k\cdots{}b_n$ that we are trying to derive and the next unconsumed/unmatched character of the input string is $b_k$ and the leftmost non-terminal symbol is $X$.

In other words, we are in the middle of some derivation like:

\[\begin{align*} S &\to \alpha_1\\ &\to \alpha_2\\ &\;\;\,\vdots{}\\ &\to b_1\ b_2\cdots{}b_{k-1}\ X\ \gamma \end{align*}\]ending with a sentential form that has some prefix of terminal symbols $b_1\ b_2 \cdots{} b_{k-1}$ followed by a non-terminal $X$ followed by some other stuff $\gamma$. If we’ve been crossing off letters have already been derived from the input string, then we are left aiming to derive next the letter $b_k$.

Suppose the grammar contains several production rules for nonterminal $X$. Which should we choose?

-

We could try to use an $X$ rule, say $X \Coloneqq \beta$, to derive a substring starting with $b_k$ directly, i.e. aiming for $X \to \beta \to^* b_k\,u$. However, there’s no point in trying to do this unless that rule is capable of deriving a string starting with $b_k$, in other words, if $a \in \first_s(\beta)$. This corresponds to condition 1 above.

-

Alternatively, we could use an $X$ rule, say $X \Coloneqq \beta$ to derive $\epsilon$, and postpone deriving a string starting with $b_k$ to the remainder of the sentential form $\gamma$, i.e. aiming for $X \to^* \epsilon$ and $\gamma \to^* b_k\ldots b_n$. This only makes sense as a strategy if (a) this $X$ rule is capable of deriving $\epsilon$ (i.e. $\nullable_s(\beta)$) and (b) it is possible to derive a string starting $a$ by using the sentential form $\gamma$ following $X$ (i.e. $a \in \follow(X)$). This corresponds to condition 2 above.

A grammar is suitable for predictive parsing if the associated parsing table $T$ contains at most one rule in each cell. This way, there is no choice about which rule to pick at any given point: either there is no possible rule to apply, or the rule is uniquely determined.

A grammar whose parsing table contains at most one rule in each cell is called LL(1).

To fill out the parse table, one just needs to consider each cell $T[X,a]$, and, for each, iterate through every $X$-rule $X \Coloneqq \beta$ of the grammar checking if conditions 1 or 2 are satisfied. Rule $X \Coloneqq \beta$ should be written in cell $T[X,a]$ iff at least one of the conditions is satisfied.

Let’s summarise the relevant properties of our example grammar:

\[\begin{array}{|c|c|}\hline \text{Nonterminal} & \text{Follow} \\\hline B & ),\,\andop,\,\orop \\\hline \end{array} \qquad \begin{array}{|c|c|}\hline \text{Rule RHS} & \text{Nullable?} & \text{First} \\\hline \tt & \times & \tt \\ \ff & \times & \ff \\ (B) & \times & ( \\ B \andop B & \times & \tt,\,\ff,\,( \\ B \orop B & \times & \tt,\,\ff,\,( \\\hline \end{array}\]Now we can construct the parsing table $T$. Let’s start with the leftmost cell which is at coordinate $[B,\,\tt]$. So we iterate through all the $B$ rules and check conditions 1 and 2 for $a$ being $\tt$ and $\beta$ being the RHS of the rule. The first $B$ rule is $B \Coloneqq \tt$, so the conditions are:

- $\tt \in \first(\tt)$

- or, $\nullable(\tt)$ and $\tt \in \follow(B)$

In this case, condition 1 is true according to (common sense, and) the first line of the table. Therefore, we add rule $B \Coloneqq \tt$ into the cell $T[B,\,\tt]$. The second rule for $B$ is $B \Coloneqq \ff$. For this rule, the conditions amount to:

- $\tt \in \first(\ff)$

- or, $\nullable(\ff)$ and $\tt \in \follow(B)$

Neither of these conditions is satisfied, so we do not add this rule into cell $[B,\,\tt]$. The next rule is $B \Coloneqq (B)$ and the parsing table conditions amount to:

- $\tt \in \first((B))$

- or, $\nullable((B))$ and $\tt \in \follow(B)$

Neither of these conditions is satisfied, so we do not add this rule into cell $[B,\,\tt]$ either. The next rule is $B \Coloneqq B \andop B$. Here the conditions are:

- $\tt \in \first(B \andop B)$

- or, $\nullable((B))$ and $\tt \in \follow(B)$

Consulting the summaries above, we see that $\tt$ is in $\first(B \andop B)$. This makes sense because starting from $B \andop B$ you can derive $\tt \andop B$ in one step. Therefore, we need to also add the rule $B \Coloneqq B \andop B$ to cell $T[B,\,\tt]$.

Similarly, we find $\tt \in \first(B \orop B)$ too and so we must also add the final rule $B \Coloneqq B \orop B$ to the cell too.

That completes are analysis of the cell $T[B,\,\tt]$ and we move onto the next. Eventually, we will have a complete parsing table:

\[\begin{array}{|c|c|c|c|c|}\hline \text{NT} & \tt & \ff & ( & ) & \andop & \orop \\\hline B & \begin{array}{c}B \Coloneqq \tt\\B\Coloneqq B \andop B\\B\Coloneqq B \orop B\end{array} & \begin{array}{c}B \Coloneqq \ff\\B\Coloneqq B \andop B\\B\Coloneqq B \orop B\end{array} & \begin{array}{c}B \Coloneqq (B)\\B\Coloneqq B \andop B\\B\Coloneqq B \orop B\end{array} & \phantom{woo} & & \phantom{woo} \\\hline \end{array}\]Therefore, the single-line $B$ grammar we have been analysing is not LL(1). In fact, the parsing table for this grammar illustrates it’s problems for predictive parsing quite directly. If the leftmost non-terminal is say, $B$ and the next unmatched character of the input is $($, then we don’t know whether to use:

- $B \Coloneqq (B)$, which would make sense if e.g. the rest of the string is $(\tt \andop \ff)$

- $B \Coloneqq B \andop B$, which would make sense if e.g. the rest of the string is $(\tt) \andop \ff$

- or $B \Coloneqq B \orop B$, which would make sense if e.g. the rest of the string is $(\tt) \orop \ff$

On the other hand, I can tell you that, for the alternative grammar:

\[\begin{array}{lcl} B &\Coloneqq& A\ B'\\ B' &\Coloneqq& \andop A\ B' \mid \mathord{\orop}\ A\ B' \mid \epsilon \\ A &\Coloneqq& \tt \mid \ff \mid (B) \end{array}\]one obtains the following parsing table:

\[\begin{array}{|c|c|c|c|c|}\hline \text{NT} & \tt & \ff & ( & ) & \andop & \orop \\\hline B & B \Coloneqq AB' & B \Coloneqq AB' & B \Coloneqq AB' & & & \\ B' & & & & B' \Coloneqq \epsilon & B' \Coloneqq \mathord{\andop}AB' & B' \Coloneqq \mathord{\orop}AB'\\ A & A \Coloneqq \tt & A \Coloneqq \ff & A \Coloneqq (B) & & & \\\hline \end{array}\]Since the table has at most one entry per cell, we can conclude that this grammar is LL(1), and it will allow us to construct a derivation for any given input string in the language of the grammar without any insight - we just consult the table to see which rule to choose at each step.

I recommend you redo the derivation for $\tt \orop \ff \andop \tt$ from above simply following the strategy described by the parsing table, rather than relying on any thought of your own.