Writing Grammars

There are two parts to this lecture: notation in order to write about grammars precisely, and some patterns that are useful when writing new grammars (i.e. designing grammars).

Mathematical Notation

It will be useful to agree some notation for discussing context free grammars a bit more precisely.

A Context Free Grammar (CFG) consists of four components:

- An alphabet of terminal symbols. We shall use $a$, $b$, $c$ and other lowercase letters as metavariables for terminals.

- A finite, non-empty set of nonterminal symbols, disjoint from the terminals. We use uppercase letters $S$, $T$, $X$ and so on as metavariables for nonterminals.

- A finite set of production rules. Each production rule has shape $X \Coloneqq \alpha$, where $\alpha$ is a sequence of terminals and non-terminals that we refer to as the right-hand side of the rule.

- A designated non-terminal called the start symbol, which we will usually write as $S$.

If you think back to the previous example, you will notice that a key part of the grammar is manipulating sequences of terminals and nonterminals, like \(\ff \andop (L \orop L)\). One could think of these as strings over the alphabet that consists of the terminals the nonterminals combined, but I would rather reserve the word string only for sequences of terminals. (Possibly) mixed sequences of terminals and nonterminals are known as sentenial forms.

A sentential form is just a finite sequence of letters, each of which is either a terminal or a nonterminal. We use lowercase greek letters $\alpha$, $\beta$, $\gamma$ and so on as metavariables for sentential forms.

We will continue to reserve metavariables $u$, $v$, $w$ and so on for strings (of terminals only).

Metavariables

We use metavariables when we want to state something that involves a string, or a sentential form that we don’t want to specify concretely. For example, we might say, “for all strings $u$, \(\abs{u^2} \geq \abs{u}\)”, or “given a sentential form of shape $\alpha 0 \beta$ (i.e. containing at least one letter $0$),…”. In other words we use them as ordinary mathematical variables in our reasoning about strings, or sentential forms.

The reason they are called meta variables is because, in mathematical logic and programming language theory, we are often talking about strings (or sentential forms) that come from languages that have their own internal notion of variable. For example, if we want to discuss strings that are C programs, then the language of C programs has its own notion of variable, namely the variables in the program. So, to not confuse these different kinds of variables: the variables that are in the language we are studying, e.g. C program variables, and the variables we use in the language we write when we are reasoning about them (this is sometimes called the metalanguage); it is standard to refer to the latter as metavariables (variables of the metalanguage).

Note: there is nothing special about the particular letters used for the nonterminals, we could have used alternative names and we would still consider it essentially the same description of the While programming language. For example, if we replaced everywhere in the rules the letter N by the letter P.

Derivation

A context free grammar is a device for defining a language (i.e. set) of strings. A string is in the language defined by a grammar just if we can use the rules of the grammar to derive it.

Derivation is a step-by-step process for transforming one sentential form into another one. A single step of a derivation, consists in transforming one sentential form $\alpha$ into another sentential form $\beta$ by replacing, in $\alpha$, exactly one occurrence of a nonterminal symbol by its right-hand side according to one of the production rules.

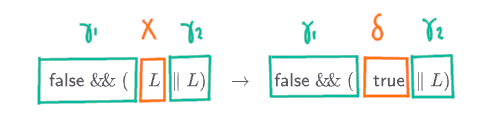

The sentential form $\alpha$ can make a derivation step to $\beta$, written $\alpha \to \beta$, just if:

- $\alpha$ has shape $\gamma_1\,X\,\gamma_2$ and $\beta$ has shape $\gamma_1\,\delta\,\gamma_2$

- and there is a production rule $X \Coloneqq \delta$ in the grammar

The best way to understand a definition of some new assertion, in this case $\alpha \to \beta$, is to think of it as telling you how to check the assertion. That is, if I gave you some random sentential forms $\alpha$ and $\beta$, how do we know if we can say $\alpha \to \beta$ ? How do you go about checking that it is a correct step?

First you would try, by comparing $\alpha$ and $\beta$, to check that the only difference between them is that some nonterminal in $\alpha$ is replaced in $\beta$ by some other bit of sentential form. A way of saying “the only difference between them” more precisely is to say that both $\alpha$ and $\beta$ start with the same sentential form, lets call it $\gamma_1$, and end with the same sentential form, lets call that $\gamma_2$, but that the bit in between $\gamma_1$ and $\gamma_2$ can be different. However, it can’t be an any old difference. The thing that changed in $\alpha$ must be a single solitary nonterminal symbol, say $X$, which was changed according to a production rule, say $X \Coloneqq \delta$, whose left-hand side is $X$. Then it had better be that the bit that is different in $\beta$ is exactly the right-hand side of this production rule, i.e. $\delta$.

Note that, since $\epsilon$ is a sentential form - the empty sentential form - the definition allows for any of $\gamma_1$, $\gamma_2$ and $\delta$ to be omitted. In the following example, we have $\gamma_1 = \gamma_2 = \epsilon$:

\[F \to L \andop F\]We can chain derivation steps together to form a derivation sequence.

A derivation sequence is a non-empty sequence of sentential forms $\alpha_1$, $\alpha_2$, … $\alpha_{k-1}$, $\alpha_k$ in which consecutive elements of the sequence are derivation steps:

\(\alpha_1 \to \alpha_2 \to \cdots{} \to \alpha_{k-1} \to \alpha_k\)

Often, we don’t care about the intermediate steps in a derivation sequence, but only that the end is reachable from the start, for which we have the notation $\alpha_1 \to^* \alpha_k$.

A sentential form $\beta$ is derivable from $\alpha$, written $\alpha \to^* \beta$ just if there is a derivation sequence starting with $\alpha$ and ending with $\beta$.

Ultimately, all this machinery is there in order for us to say precisely which strings constitute the language defined by the grammar.

The language of a grammar $G$, written $L(G)$, is the set of all strings $w$ derivable from the start symbol, i.e. \(\{\, w \mid S \to^* w \,\}\).

Grammars can Express Sequences

Suppose we want to design a grammar to define the language of all possible sequences of digits (0-9), including the empty sequence. A useful approach is to think of a sequence of digits as a Haskell or OCaml list, which is either empty, or consists of at least one element - the head, a digit, - and a possibly empty sequence of further elements - the tail, itself a sequence of digits. This approach gives rise to the following grammar:

\[\begin{array}{rcl} \nt{Digit} &\Coloneqq& 0 \mid 1 \mid 2 \mid 3 \mid 4 \mid 5 \mid 6 \mid 7 \mid 8 \mid 9\\[2mm] \nt{Digits} &\Coloneqq& \nt{Digit}\ \nt{Digits} \mid \epsilon \end{array}\]For example:

\[\begin{array}{rll} \nt{Digits} &\to& \nt{Digit}\ \nt{Digits}\\ &\to& \nt{Digit}\ \nt{Digit}\ \nt{Digits}\\ &\to& \nt{Digit}\ \nt{Digit}\ \nt{Digit}\ \nt{Digits}\\ &\to& \nt{Digit}\ \nt{Digit}\ \nt{Digit}\\ &\to^*& 1\ 2\ 3 \end{array}\]The same pattern works no matter how complex the elements of the sequence can be (as long as they can themselves be described by production rules). Recall the production rules defining Boolean expressions starting from $\nt{B}$, by adding the following extra rule, we can describe all sequences of them with a nonterminal $\nt{Bs}$:

\[\begin{array}{rcl} \nt{Bs} &\Coloneqq& \nt{B}\ \nt{Bs} \mid \epsilon \end{array}\]Suppose we want to describe non-negative integers, that is, non empty sequences of digits. We can build this out of our description of (possibly empty) sequences of digits by saying that a number is a digit followed by a (possibly empty) sequence of digits:

\[\begin{array}{rcl} \nt{Digit} &\Coloneqq& 0 \mid 1 \mid 2 \mid 3 \mid 4 \mid 5 \mid 6 \mid 7 \mid 8 \mid 9\\[2mm] \nt{Digits} &\Coloneqq& \nt{Digit}\ \nt{Digits} \mid \epsilon\\[2mm] \nt{Number} &\Coloneqq& \nt{Digit}\ \nt{Digits} \end{array}\]Describing sequences is so useful in the definition of programming languages that often we use some special notation to save us having to use this pattern over and over again. The notation: \([\alpha]^*\) when used on the right-hand side of a production rule means “any finite sequence of $\alpha$”. We will omit the square brackets if $\alpha$ is just a single symbol. So, non-negative integers can be defined by:

\[\begin{array}{rcl} \nt{Digit} &\Coloneqq& 0 \mid 1 \mid 2 \mid 3 \mid 4 \mid 5 \mid 6 \mid 7 \mid 8 \mid 9\\[2mm] \nt{Number} &\Coloneqq& \nt{Digit}\ \nt{Digit}^* \end{array}\]A non-empty comma-separated list of digits can be described by:

\[\begin{array}{rcl} \nt{Digit} &\Coloneqq& 0 \mid 1 \mid 2 \mid 3 \mid 4 \mid 5 \mid 6 \mid 7 \mid 8 \mid 9\\[2mm] \nt{DigitList} &\Coloneqq& \nt{Digit}\ [,\ \nt{Digit}]^* \end{array}\]This new notation doesn’t really add anything to grammars, because we can always eliminate any occurrence of \([\alpha]^*\) by introducing two new non-terminals, say $X$ and $\nt{Xs}$, and the rules $X \Coloneqq \alpha$ and $\nt{Xs} \Coloneqq X\ \nt{Xs} \mid \epsilon$, and finally replacing \([\alpha]^*\) by simply $Xs$.

\[\begin{array}{rcl} \nt{Digit} &\Coloneqq& 0 \mid 1 \mid 2 \mid 3 \mid 4 \mid 5 \mid 6 \mid 7 \mid 8 \mid 9\\[2mm] \nt{DigitList} &\Coloneqq& \nt{Digit}\ \nt{Xs}\\[2mm] \nt{X} &\Coloneqq& ,\ \nt{Digit}\\[2mm] \nt{Xs} &\Coloneqq& \nt{X}\ \nt{Xs} \mid \epsilon \end{array}\]So, if you want to construct a derivation involving the notation $[\alpha]^*$, just remember that it is a shorthand for some non-terminal $\nt{Xs}$ defined as above, and so the only thing we can really do is to say that it derives any finite sequence of $\alpha$ over some number of steps. For example, we can derive exactly three $\alpha$:

\[[\alpha]^* \to^* \alpha\ \alpha\ \alpha\]Other Useful Patterns

We discuss the following examples over alphabet \(\{0,1\}\) (most are from Sipser Ex. 2.4), which shows some of the common patterns when formulating a CFG.

\[\{ w \mid \text{$w$ is any word over $\{0,1\}$}\}\]

A grammar for this language is:

\[S \Coloneqq 0\ S \mid 1\ S \mid \epsilon\]Each derivation step consists of either extending the current sentential form by any choice of digit 0 or 1, or ending the string with epsilon. Thus, any possible word can be derived.

Or, using our new notation:

\[\begin{array}{rcl} S &\Coloneqq& B^*\\ B &\Coloneqq& 0 \mid 1 \end{array}\]\[\{ w \mid \text{$w$ contains at least three letter 1} \}\]

A grammar for this language is:

\[\begin{array}{rcl} S &\Coloneqq& A\ 1\ A\ 1\ A\ 1\ A\\ A &\Coloneqq& 0\ A \mid 1\ A \mid \epsilon \end{array}\]A word derivable from S must include 3 1s, because there is only one rule possible which introduces them. Around the 1s you may put any words you like because we only require “at least” 3, so the rules for $A$ are exactly the same as in the previous example. If you wanted to express the language of words with exactly 3 1s, then you can remove the $A \Coloneqq 1\ A$ production, so that the words allowed between the 1s cannot contain 1.

\[\{ w \mid \text{$w$ starts and ends with the same symbol} \}\]

A grammar for this language is:

\[\begin{array}{rcl} S &\Coloneqq& 0 A 0 \mid 1 A 1 \mid 0 \mid 1 \mid \epsilon A &\Coloneqq& 0\ A \mid 1\ A \mid \epsilon \end{array}\]If you look at the shape of words derivable from $S$, they are forced to start and end with the same letter. For words of length 2 or more, between the first and last letter we allow any substring.

\[\{ w \mid \text{the length of $w$ is odd and its middle letter is $0$}\}\]

A grammar for this language is:

\[\begin{array}{rcl} S &\Coloneqq& X\ S\ X \mid 0\\ X &\Coloneqq& 0 \mid 1 \end{array}\]When we use the first production rule for $S$ we always add two terminal symbols onto our sentential form (we replace $S$ by $XSX$ and each $X$ derives exactly one terminal symbol). Thus, using this first rule preserves the parity (even or odd) of the length of our sentential form. In the base case we allow for $S$ being replaced by $0$ which is a length 1 string - i.e. odd. So, $S$ must derive odd length strings. In each sentential form derivable from $S$, except for the last, there will be exactly one occurrence of $S$ and it will be the exact middle of the string. Hence, when we finally replace this $S$ by 0 we guarantee that $0$ must be the middle letter of the derived string.

\[\{ w \mid \text{$w$ is a palindrome (i.e. the same word when reversed)}\}\]

A grammar for this string is:

\[S \Coloneqq 0\ S\ 0 \mid 1\ S\ 1 \mid 0 \mid 1 \mid \epsilon\]Here again, the middle of each sentential form (of length > 1) will be $S$ and using the first two rules ensures that the letter $k$ positions to the left of this mid-point will be the same as the letter $k$ positions to the right (for any $k$ appropriate to the length of the sentential form). Hence, a derivable string is certain to be a palindrome.

\[\{uv \mid |u| = |v| \text{ and } u \neq v^R\}\]

Here $v^R$ is the reverse of $v$. A grammar for this language is: