Abstract Syntax Trees

However, it is a bit generous to call the implementation of the previous chapter a parser. Usually we expect that a parser does not only recognise whether a string is in the language or not, but in the former case, it constructs some abstract, internal representation of the piece of syntax in memory. This is then used in other parts of the language translator (interpreter, compiler etc) to actually effect the translation (e.g. generate code).

Of course, we could just use the string itself as out internal representation. However, since most of the languages for which we want to parse are more structured, it is convenient to use a representation that makes this structure explicit. Moreover, the concrete syntax (the string) contains a lot of information which is not essential to understanding the fundamental structure. A standard approach is to instead use abstract syntax trees or ASTs for short.

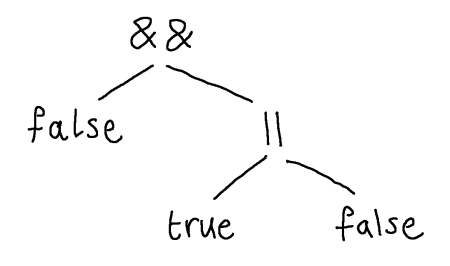

Our Boolean expressions of the previous lecture naturally have a tree structure. The expression false && (true || false) can be understood as the tree:

Notice that, in the abstract syntax tree, we have discarded the parentheses that were around the subexpression true || false. The parentheses serve only to describe the structure that is already present in the tree, namely that the right-hand argument to && is true || true.

The way to think about abstract syntax trees is as follows. A given node describes some syntactic construct in the language, like an and-expression or a truth value. If a node has a child, then this child is a component of that syntactic construct. So, here we have an and-expression with two components, a truth value false and another expression true || false. That expression is itself an or-expression, i.e. the root is || and it has two components, the true literal and the false literal.

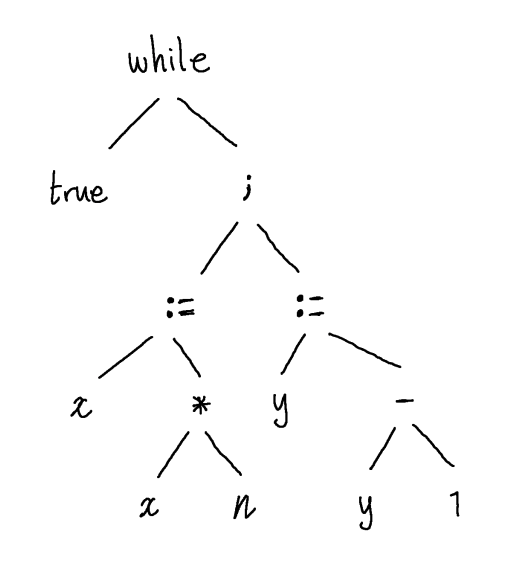

Expressions of all kinds have a very natural tree structure which we are, to some extent, already used to from school mathematics. However, with understanding of the previous paragraph, we can see that all kinds of program constructs can be naturally endowed with tree structure. For example, we may represent the following concrete syntax (i.e. string) while true do {x:= x * n; y:= y - 1} by the following AST:

In other words, this piece of syntax is a while loop, which has two components, the guard true and the body x:=x*n; y:=y-1. The body is itself a sequencing statement which has two components, the first expression in the sequence, x:=x*n and the second y:=y-1. Each of these is an assignment statement and assignment statements have two components, the variable being assigned to and the expression whose value should be assigned, etc.

There are no hard and fast rules about how to design your abstract syntax tree data structure, to some extent it will depend on what you want to do with your syntax in the rest of the software after parsing. However, a good rule of thumb is that the abstract syntax tree should capture just the essential structure of the piece of syntax you are interested in. To see what I mean by this, consider the same while loop expressed in the concrete syntax of various programming languages.

1

2

3

4

while (true) {

x = x * n;

y = y - 1;

}

1

2

3

while true:

x = x * n

y = y - 1

1

2

3

4

while true do

x := !x * n

y := !y - 1

done

1

2

3

4

while true loop

x := x * n;

y := y - 1;

end loop

Each has its own syntactic peculiarities, some use braces, some parentheses, some use the keyword “do” and some don’t. However, the essential information is the same:

- It’s a while loop.

- There is a loop guard (which is just true).

- There is a loop body (which assigns x*n to x and then y-1 to y).

And these three pieces of information are exactly what we get in the abstract syntax tree.

I mean that this is the essential information in the sense that if you forget what the loops look like in their syntax but I tell you the contents of points 1-3, then you can recreate the syntax in whichever language you are interested in. For example, if I tell you points 1-3 above, and then ask you to write the loop in C, then you can reconstruct (modulo whitespace and unnecessary bracketing) the first piece of syntax above. On the other hand, if I omitted any one of 1-3, say 2, then you could not possibly know what the loop looked like when written in C in the original syntax.

The Brischeme Abstract Syntax Tree

In OCaml, like most functional programming languages, tree data structures are standard. Every algebraic data type (variant type) is really a tree data structure and should be thought of that way. In the Brischeme interpreter, the AST is given by four types:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

(** [primop] is an enumeration of the available primitive operations. *)

type primop =

| Plus

| Minus

| Times

| Divide

| Eq

| Less

| If

| And

| Or

| Not

(** A [form] is either a top-level definition or an expression to be evaluated .*)

type form =

| Define of string * sexp

| Expr of sexp

(** A [sexp] is an expression to be evaluated. *)

and sexp =

| Bool of bool

| Num of int

| Ident of string

| Lambda of string list * sexp

| Call of primop * sexp list

| App of sexp * sexp list

(** A [prog] is just a list of [form]. *)

type prog = form list

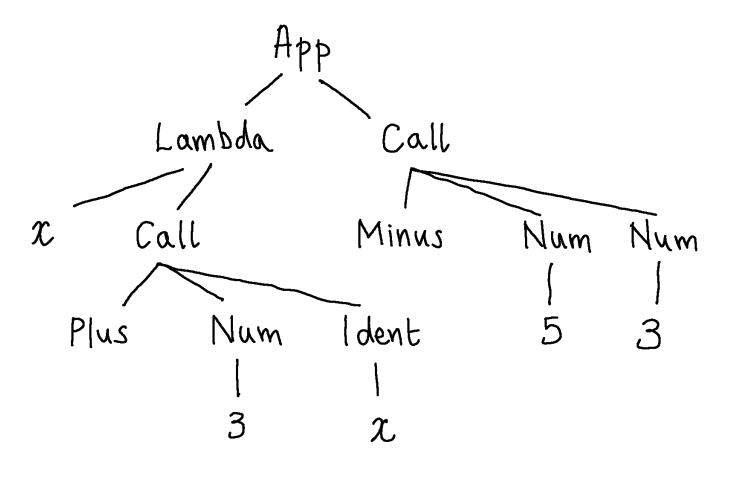

The values of these datatypes are, of course, those OCaml expressions that can be formed from the constructors (and their arguments). Here are four values of type sexp:

1

2

3

4

5

Num 3

Ident "foo"

Call (Plus, [Num 3, Ident "x"])

Lambda (x, (Call (Plus, [Num 3, Ident x])))

App (Lambda (x, (Call (Plus, [Num 3, Ident x]))), [Call (Minus, [Num 5; Num 3])])

but generally it is a good idea to think of these values really as describing trees in which the arguments to a constructor form its children:

In fact, when functional programmers write libraries, say a new library for X, they will often think that they are really designing a language for describing X-things (and their principle operations), and the key data type for X-things describes their abstract syntax.

Precedence and Associativity

The abstract syntax of a language is really an internal representation, and so one would expect it to be completely hidden to the programmer. However, there is an important way in which it leaks through, and that is via operator precedence and associativity.

Associativity

The associativity of an operator is the name given to a convention used when inserting implicit parentheses (building abstract syntax trees). An operator $\oplus$ is said to be left associative if a chain $u \oplus v \oplus w$ should be considered syntactically identical to $(u \oplus v) \oplus w$, that is, having the same abstract syntax tree. An operator $\oplus$ is said to be right associative if a chain $u \oplus v \oplus w$ is considered syntactically identical to $u \oplus (v \oplus w)$.

Note, this is a syntactic property of operators and is different from the semantic property of being associative, which you will have come across in mathematics. If an operator is associative this means that the value of $(u \oplus v) \oplus w$ is the same as the value of $u \oplus (v \oplus w)$, i.e. they evaluate to the same thing - they have the same semantics. In the notation you will learn in part 2 of this unit, we would write \([\![(u \oplus v) \oplus w]\!] = [\![u \oplus (v \oplus w)]\!]\) for this. So, if an operator is associative, then it doesn’t really matter whether it associates right or left in the syntax, because no matter how we insert the implicit parentheses the same value will be obtained. However, even in this case, we still need to make a choice in the parser in order to build the AST one way or another.

Note: in Brischeme (and other Scheme languages) all operator calls are required to be explicitly parenthesised, so a chain like $3 + 4 + 5$ is simply invalid. Thus, associativity is a non-issue in the Brischeme language. However, in most other programming languages, an expression like $3 + 4 + 5$, or a type like $\mathsf{Int} \to \mathsf{Int} \to \mathsf{Int}$ is valid syntax, and then we have to confront the question of what is meant by it.

Precedence

Associativity refers to how to understand the structure of expressions made of a single operators (in some cases, it can also be used for chains of several “similar” operators - we will see what “similar” means shortly). However, it does not on its own allow us to disambiguate the structure of an expression involving a chain of different operators.

For example, it is a common convention (though not universal) that the numerical operators “+” and “*” associate to the left. E.g.

\[\begin{array}{lcr} 3 + 4 + 5 & \text{is identical to} & 3 + (4 + 5)\\ 3 * 4 * 5 & \text{is identical to} & 3 * (4 * 5) \end{array}\]However, this is not enough to disambiguate mixed chains involving both operators: that is, to understand their structure - what is an argument of what? Consider the following two strings:

\[3 + 4 * 5 \qquad 4 * 5 + 3\]If we were to simply say that these chains are left associated, because both the operators are, then we will end up with (ASTs corresponding to the following parenthesisation):

\[(3 + 4) * 5 \qquad (4 * 5) + 3\]which cannot be right, because then the expression on the left will evaluate to 12 and the expression on the right will evaluate to 23. Yet, we expect the original, unparenthesized, expressions to evaluate to the same thing. A similar problem would arise if we blindly associated to the right.

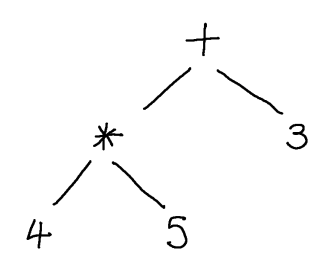

There is a different phenomenon at play in such examples, which is called operator precedence, or binding strength. In arithmetic, it is a common convention that the multiplication operator binds more tightly than the addition operator, we also say that multiplication has higher precedence. This means that, when we have an expression $4 * 5 + 3$ in which the multiplication operator $*$ and the addition operator $+$ are fighting over who gets their (seemingly) common argument $5$, multiplication grabs this argument (binds) more tightly and wins the struggle, i.e. the expression is resolved as \((4 * 5) + 3\).

The precedence of an operator is a convention used when inserting implicit parentheses (building abstract syntax trees). An operator $\otimes$ is said to be of higher precedence than an operator $\oplus$ just if every chain $u \otimes v \oplus w$ is considered syntactically identical to (that is, having the same abstract syntax as) $(u \otimes v) \oplus w$; and $u \oplus v \otimes w$ is considered syntactically identical to $u \oplus (v \otimes w)$.

In terms of the abstract syntax trees that we want to construct, we therefore want a string like $4 * 5 + 3$ to yield:

Unfortunately, this is a bit difficult to achieve without designing it into the grammar specifically. Following the approach of the previous lecture for obtaining LL(1) grammars, we would construct a grammar for * and + expressions such as:

\[\begin{array}{rcl} A &\Coloneqq& L\ R\\ R &\Coloneqq& \tm{+}\ L\ R \mid \tm{*}\ L\ R \mid \epsilon\\ L &\Coloneqq& \tm{num} \mid (\ A\ ) \end{array}\]and this would give rise to parsing functions like:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

let rec parse_l () : exp =

match peek () with

| TkNum n -> ENum n

| TkLParen ->

eat TkLParen;

let e = parse_a in

eat TkRParen;

e

and parse_r () : (primop * exp) list =

| TkPrimop p ->

eat (TkPrimop p);

let e = parse_l () in

let rs = parse_r () in

(p, e) :: rs

and parse_a() : exp =

match peek () with

| TkNum _ | TkLParen ->

let e = parse_l () in

let es = parse_r () in

???

When we parse a complex expression from $A$, we will obtain the first argument in the chain and then the rest of the chain as a list of operator-operand pairs. It’s then a little bit complex to try to piece together what the corresponding syntax tree should be, e.g. you have this list, what is going to be the root of the tree?

A different approach builds the precedence of operators into the (LL(1)) grammar. The idea is to replace the single non-terminal $A$ for arithmetic expressions by two separate non-terminals: say $F$ for factors (subchains of addition operations) and $T$ for terms (chains of multiplication operations), and then to reformulate the grammar so that factors can be bare (that is, without enclosing parens) inside a term but not vice versa.

\[\begin{array}{rcl} T &\longrightarrow& F\ T' \\ T' &\longrightarrow& \tm{+}\ F\ T' \mid \epsilon \\ F &\longrightarrow& L\ F' \\ F' &\longrightarrow& \tm{*}\ L\ F' \mid \epsilon \\ L &\longrightarrow& \tm{num} \mid (T) \end{array}\]If we want an expression that represents a factor, one of whose arguments is itself an addition, then we must use parentheses explicitly in the string, as in $(3 + 4) * 5$.

Note: we didn’t change the language of the grammar when we made this modification - both grammars describe the same language, which includes the string $3 + 4 * 5$ - we merely tightened up the internal structure so that this string can only be derived from $T$ (i.e. we consider it, overall, to be an addition) and not from $F$ (i.e. it is not a multiplication). This will make it easier for the implementation of the parser to produce the correct AST, because we want the top node of this AST to be an $+$ node (which it makes sense to return from the parsing function for $T$).

In general, if you want to design a grammar for implementation by a predictive parser, then you should first organise any operators you have into a precendence order. The precedence order is a way of stating which operators bind tighter than others. For example, in OCaml, we can look in the manual for the following operator precedence table:

| Operators | Associativity |

| ! ~ | none |

| .() .[] .{} | none |

| # | left |

| application | left |

| - | none |

| ** lsl lsr asr | right |

| * / % mod land lor lxor | left |

| + - | left |

| :: | right |

| @ ^ | right |

| = < > $ & | != | left |

| && | right |

| || | right |

| , | none |

| <- := | right |

| if | none |

| ; | right |

Operators further up the table have higher precedence than those below them, that is, they bind more tightly to their arguments. Some operators can have the same precedence - like $+$ and $-$ in OCaml. That’s fine, but binary operators with the same precedence should have the same associativity, and this will disambiguate their usage.

Once you have worked out the order of precedence of your operators, there is a standard approach to fitting them into the grammar. For each precedence level i.e. row in the table, say $i$, your grammar should have a distinct non-terminal symbol $A_i$, which produces expressions formed from that operator. If some operators of a higher precedence, say $j > i$, are allowed to be nested (without parenthesisation, since they bind tighter) inside those of level $i$, then the arguments of the operator will be described by $A_j$ in the production rule for $A_i$.

In our example, multiplication binds tighter than addition, and we have a dedicated non-terminal for each, and the production rule for additions $T$ creates sequences each of whose elements is a multiplication $F$.